Why don’t we learn from history? This is the question B.H. Liddell Hart posed to the world in 1944. In fact, he devoted an entire book to it.

Written during the final years of World War II, Why Don’t We Learn from History exposes one of humankind’s most costly flaws: our willful ignorance toward the past.

Hart, a military historian, understood the danger of allowing novelty and emotion to obscure the lessons our ancestors learned the hard way. His concerns echoed those of the philosopher George Santayana, who, just before World War I, warned that those who do not study the past are doomed to repeat it.

Now, here we are in 2020 with the internet in our pockets, self-parking cars, and swarms of researchers dedicated to cracking the codes for productivity, relationships, and happiness. And yet, we’re more stressed, time-strapped, and confused than ever.

Does this prove that we’re stupid or failures? No, but it may prove that we’re searching for answers in the wrong places.

In college, I asked a mentor for some career advice. His answer flipped my world upside down: “You don’t need advice, you need information.”

Advice is speculative and tainted with biases. Information, on the other hand, has historical precedent. You can translate information into advice, but not always the other way around. It’s the difference between asking: “What should I do?” and “Do you know anyone who has experienced [INSERT PROBLEM HERE]?”

The point is that we need to seek information that has stood the test of time, to scour through the classics before we scour through Twitter. We spend countless hours studying Ted Talks, life hacks, and anecdotal evidence geared toward decoding the human condition. Meanwhile, we’re sitting on centuries of wisdom, most of which is untapped.

It’s like we’re stuck on an island, scrambling to build a raft out of driftwood while there’s a lifeboat boat within eyesight.

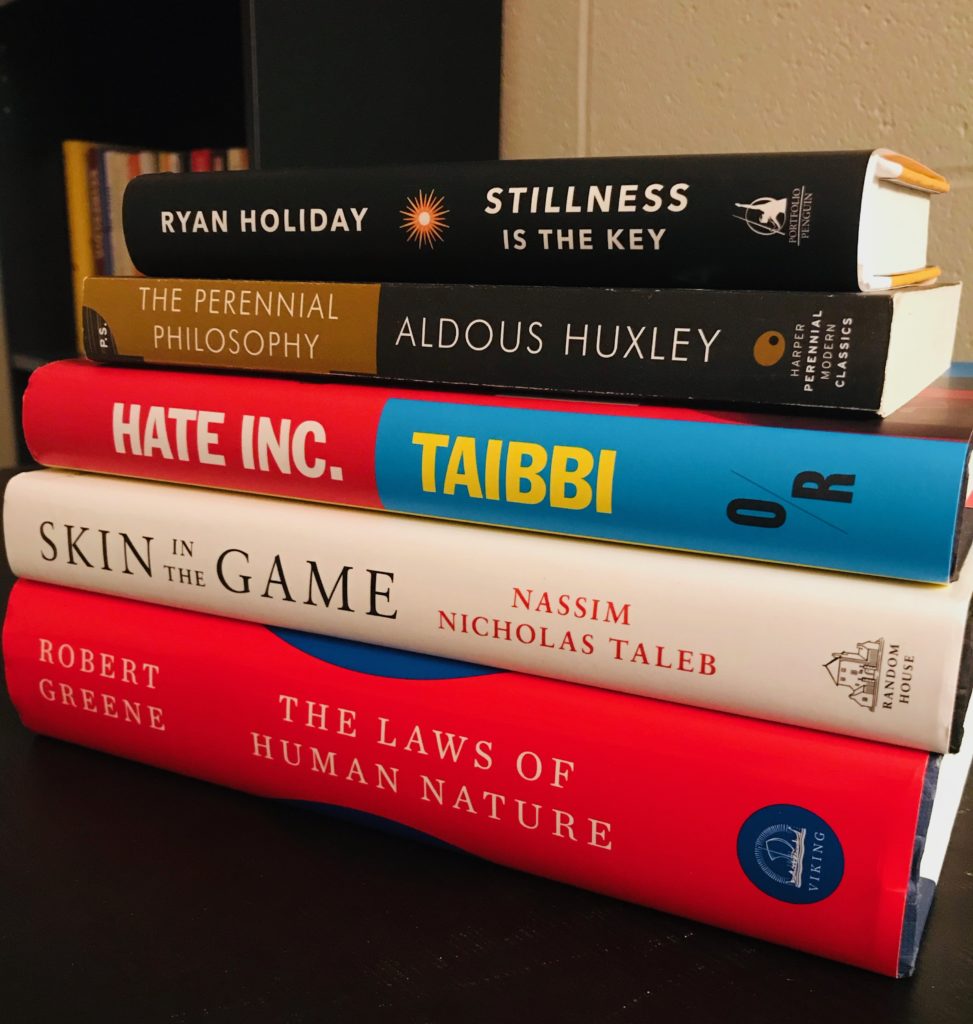

“Whatever problem you’re struggling with is probably addressed in some book somewhere written by someone a lot smarter than you,” says the author Ryan Holiday. “People have been moving West, leaving school, investing their savings, getting dumped or filing for divorce, starting businesses, quitting their jobs, fighting, and dying for thousands of years. This is all written down, often in the first person. Read it.”

Bingo.

But maybe you don’t have time to read 1,000-page biographies. Or maybe you do have time, but don’t know where to start. Or maybe you’re juggling two jobs, debt, kids, bills, and you just need the answers.

I’m privileged to have the bandwidth to read a lot of books — it’s part of my job. As a result, I have thousands of index cards filled with stories, quotes, and anecdotes. They weren’t doing any good collecting dust, so I started a monthly newsletter that leverages history to navigate modern issues.

It’s called New Problems / Old Answers: Practical History for People in a Hurry.

Navigating office politics, reasoning with problematic people, avoiding distractions, controlling emotions, managing money — we have to deal with all of this, but so did people hundreds or even thousands of years ago. Sometimes their experiences instruct us what to do, other times it’s what to avoid. Regardless, we’d be foolish not to learn from them.

The emails are always free, always less than 400 words, and consist of two parts: “A Quick Story” and “Why It Matters.” The lessons probably won’t make you rich, eliminate your fears, or solve all of your interpersonal conflicts. But they will refine your strategic thinking. You can’t solve specific problems unless you’re rooted in general principles that have stood the test of time.

As Mark Twain quipped, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

If you want the New Problems/Old Answers newsletter, sign up below.

Make no mistake: Successful students usually become successful adults, albeit in tightly restricted niches that promise six figure salaries and “stability.” But as psychologist Ellen Winner points out, only a fraction of gifted children evolve into revolutionary adult creators.

Make no mistake: Successful students usually become successful adults, albeit in tightly restricted niches that promise six figure salaries and “stability.” But as psychologist Ellen Winner points out, only a fraction of gifted children evolve into revolutionary adult creators. In the spring of 1802, a Scottish lawyer and aspiring writer named Walter Scott sustained an injury that would ultimately catapult his career. The 31-year-old was kicked by a horse, a tragedy that confined him to his bed for nearly a month. But rather than writing in self-pity, Walter Scott picked up a pen.

In the spring of 1802, a Scottish lawyer and aspiring writer named Walter Scott sustained an injury that would ultimately catapult his career. The 31-year-old was kicked by a horse, a tragedy that confined him to his bed for nearly a month. But rather than writing in self-pity, Walter Scott picked up a pen.